Here’s a wonderful, festive, royalty-free stock photo I got by searching for “thanksgiving” on a stock photo site:

Now, just how did that photo get from the server hosting our blog to your computer? I’m going to break down a core part of the internet for you: routing!

A Series of Tubes

There have been many attempts at analogies that help explain the complex nature of the Internet to laypeople. Late Alaskan Senator Ted Stephens explained it as “a series of tubes.” I’ve also heard of it explained using the metaphor of both how electricity and water supply systems work, as well as the post office, highway, and phone system. The truth is that it’s a little like all those things, but it’s perhaps most like the phone system, because it was originally an extension of the phone system (as anyone who remembers modem sounds from the days of AOL can attest).

The internet itself is made up of thousands of smaller networks that are all interconnected. Comcast, AT&T, Verizon, and RCN are all examples of what are called Tier 3 networks, where their traffic is mostly things coming in (as you download, stream, and access websites). Tier 1 networks connect to others and serve as an internet backbone. Tier 2 providers lie somewhere in the middle.

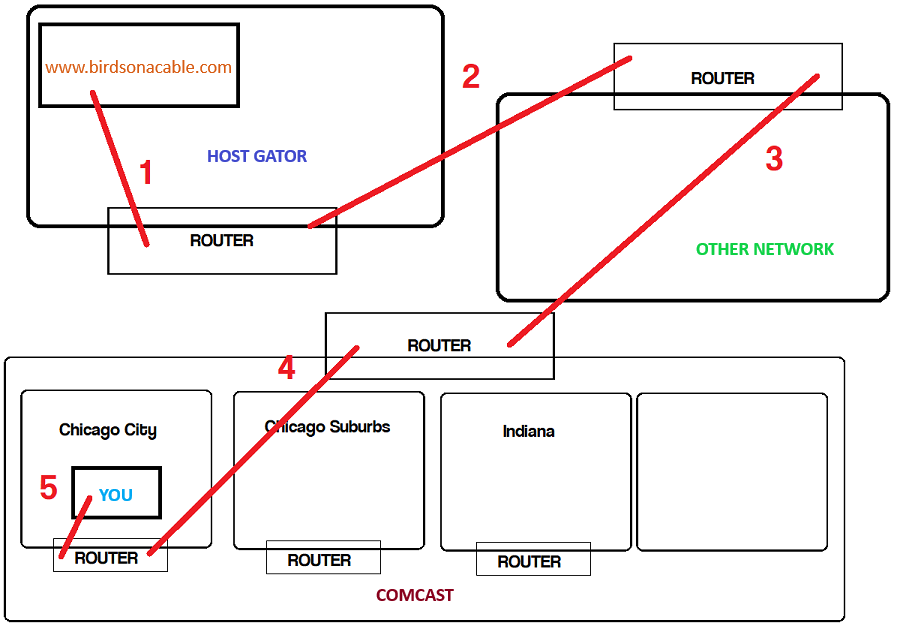

Now, for an amount of data (part of a YouTube video or that very festive Thanksgiving image) to traverse those networks, there needs to be some sort of intelligence to guide the way.

Addresses

You’ve likely heard about IP addresses, and maybe you’ve even been asked to find yours. Every device that’s connected to the internet has an IP address. This includes phones, servers, and computers. An IPv4 address (the current most common standard) consists of 32 bits of information, displayed as four numbers between 0 and 255, such as 8.8.8.8 (Google’s DNS Server Address) or 192.185.71.128 (The IP address for the Birds on a Cable Website). It’s displayed that way instead of just a simple number from 1 to 4,294,967,295 (where Google’s DNS would be 134,744,072 and Birds on a Cable would be 1,616,693,120) because it makes the next idea I’m going to explain simpler: subnets.

Because of hardware limitations, once there were hundreds of thousands of people using the internet, it was impossible for every computer to know the direct path to every other computer; computers didn’t have the memory required at the time. Networks were given specific blocks of IP addresses to use. HP, Apple, Ford, MIT, the USPS, and the DOD all have or had giant blocks of 16 million+ IP addresses each (most of those groups have since given back the majority of their IPs, as they don’t need millions). Most ISPs have smaller blocks than that, numbering in the hundreds of thousands or less.

At the edge of their networks, where they connect to other networks in the internet, each company or entity has equipment known as routers. These routers can keep information about larger blocks of IPs in order. Much like a package destined for the suburbs of Chicago first makes a stop in Chicago, traffic destined for your home computer is first sent to the main router for your ISP. It may be that Comcast, for instance, doesn’t have a direct connection to the network hosting Birds on a Cable’s website, but each network knows which direction to send the traffic such that it will be passed along in an efficient manner to get to the final stop. Some of this technology is automatic and learning, adapting to changes in traffic so that routes that become congested are given a lower priority, but the fixed links between networks tend to be static and manually created, as they are tied to physical connections between these networks. This is how large sections of the internet can go down when a backbone line is cut, but the outage can be routed around in a matter of hours by altering routes to go the long way.

Tying It All Together

The internet is not one massive network. It’s a series of large networks all run by companies, governments, and groups that are interconnected, with routers at each end of a connection. These routers are aware of each other, and each router has a guide to how to get from itself to anywhere else. They also have internal guides to know how to get traffic that’s meant for people and equipment inside to where it needs to go. This allows your computer to ask our server for a Thanksgiving image from almost anywhere in the world, and in seconds you’ll have it displayed in your browser.